The United States has finalized a significant retirement age shift, pushing the full retirement age for Social Security benefits beyond the long-standing age-67 benchmark. The change, developed through existing statutory frameworks and administrative adjustments, aims to stabilize the program as demographic changes strain federal retirement financing.

Retirement Age Shift

| Key Fact | Detail |

|---|---|

| FRA rises | Full retirement age climbs from 67 to as high as 68 over coming years |

| Reason for change | Longevity gains and funding pressures drive revisions |

| Early claiming remains | Benefits still available at 62 but with steeper reductions |

| Program at risk | Trust fund reserves projected to diminish by early 2030s |

Understanding the Retirement Age Shift

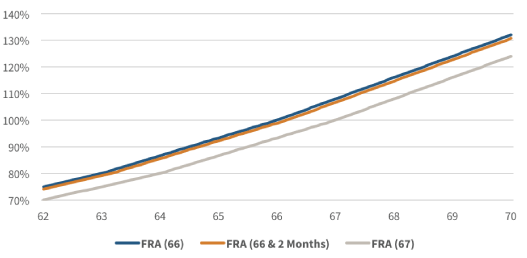

The retirement age shift affects how and when Americans born after 1960 can access full Social Security benefits. According to the Social Security Administration (SSA), new phased adjustments will increase the full retirement age (FRA) beyond 67, reaching 67 years and four months for some groups and eventually rising to 68 for younger cohorts.

SSA officials say the update aligns with demographic trends. “Americans today live longer, healthier lives, which extends the period during which they collect benefits,” an SSA spokesperson wrote in a statement.

Economists argue that delaying the FRA is one of the least disruptive tools for slowing benefit growth. However, critics contend it indirectly reduces benefits, especially for workers unable to continue working late into their 60s.

How the FRA Change Works

The FRA will continue rising in incremental steps:

Specific Age Changes by Birth Year

- Born 1960–1964: FRA increases from 67 to 67 years and 4 months.

- Born 1965–1969: FRA rises to 67 years and 8 months.

- Born 1970–1974: FRA reaches approximately 68.

- Born 1975 and later: FRA stabilizes near 68 but may rise further depending on future legislation.

While FRA is increasing, early retirement at age 62 remains intact. The change affects only when workers become eligible for full benefits.

Impact on Early Retirement and Benefit Reductions

A central effect of the retirement age shift is a deeper benefit reduction for people who claim early.

The SSA explains that filing before FRA permanently reduces monthly payments. As the FRA rises, these reductions grow because the benefit formula assumes a longer payout period.

For example:

- Claiming at 62 under an FRA of 67 results in a 30% cut.

- Claiming at 62 under an FRA of 68 could result in a reduction of more than 33%.

Dr. Teresa Ghilarducci, a retirement expert at The New School, said raising the FRA “places the greatest burden on workers in physically demanding jobs who cannot delay retirement, even when economic incentives push them to.”

Why the Rule Is Changing Now

Demographic Pressures

According to the SSA Trustees, the number of retirees is growing faster than the number of workers. Baby boomers are aging into benefits, while birth rates remain at historic lows. As a result, fewer workers are contributing payroll taxes to support the system.

Longer Life Expectancy

In 1940, the average retiree collected benefits for about 12 years. Today, retirees collect for more than 20 years on average, according to federal actuarial data.

Funding Concerns

The 2024 Trustees Report projects that without policy changes, the combined trust funds will deplete around the early 2030s. At that point, incoming payroll taxes could cover only about 77% of scheduled benefits.

Raising the FRA stretches benefit payouts over a shorter period, reducing total lifetime payments and slowing trust fund depletion.

Political Debate and Public Reaction

The retirement age shift has sparked debate across political lines.

Labor groups like the AFL-CIO argue the change disproportionately affects workers with lower incomes and those in manual labor. They note these workers often have fewer years of healthy work capacity and smaller retirement savings.

On the other hand, fiscal conservatives view higher retirement ages as a practical reform. Andrew Biggs, a retirement policy scholar, has argued that “incremental FRA increases help balance the system without requiring steep tax hikes.”

The White House has not endorsed broader FRA increases but acknowledges the need for bipartisan reform.

Polling from Pew Research Center shows that a majority of Americans oppose raising the FRA but support measures like raising the cap on taxable wages, suggesting public preference for alternative funding solutions.

Historical Context: How the FRA Has Evolved

The FRA has changed only twice in U.S. history:

Original FRA of 65 (1935–1983)

When Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the Social Security Act in 1935, the FRA was set at 65. Only a small portion of the population reached that age during the era.

1983 Amendments Under Reagan

Congress raised the FRA to 67 for future generations to address a near-term funding crisis. The increase was gradual, spanning more than four decades.

Current Adjustment

Unlike previous changes driven by legislative action, the new shift is implemented through administrative mechanisms within existing statutory constraints. It follows actuarial trends but stops short of a full legislative overhaul.

Economic and Social Implications

Potential Labor Market Effects

Increasing the FRA could keep older Americans in the workforce longer. Economists suggest this may reduce labor shortages in sectors such as healthcare, education, and service industries. However, it may also increase age-related workplace injuries.

Impact on Low-Income and Minority Groups

Studies show that lower-income workers often have shorter life expectancies. For these groups, raising the FRA reduces lifetime Social Security benefits more sharply because they are more likely to claim early.

Gender Considerations

Women, who statistically live longer and participate in part-time work more frequently, may face increased financial vulnerability as FRA rises. Advocacy groups emphasize the need for strengthened auxiliary benefits.

Case Study: How the Change Affects Real Workers

Maria, 61, Nurse

Maria has worked as a registered nurse for 35 years. She planned to retire at 65, but under the new rule her FRA will be nearly 68. She says her work is rewarding but physically demanding.

“This job is tough on the body,” she said. “I don’t know if I can safely work another six or seven years.”

David, 52, Software Engineer

David’s FRA will be 68. He says the adjustment does not change his long-term plans and expects to continue working into his late 60s.

“As long as I have the flexibility to work remotely, extending my career feels manageable,” he said.

These stories reflect a growing disparity in how retirement age changes affect different professions and income groups.

How the U.S. Compares Internationally

Many industrialized nations have already raised retirement ages:

| Country | Retirement Age | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| United Kingdom | 66, rising to 67 | Further increases tied to longevity |

| Germany | 66, rising to 67 | Gradual rise through 2031 |

| Japan | 65 | Encouraging work to 70 as an option |

| Australia | 67 | Increased between 2017 and 2023 |

The United States remains in line with global trends but has not yet tied its retirement age to life expectancy, a mechanism several nations now use.

Social Security & VA Beneficiaries Alert: New 2025 Scams You Need to Watch For

Preparing for the New FRA: What Workers Should Consider

Financial advisors recommend several steps:

Review Benefit Estimates

Workers should use the official SSA benefits portal to see updated projections based on the new FRA.

Adjust Savings Plans

With later FRA thresholds, increasing personal savings through 401(k)s or IRAs becomes more critical.

Consider Health Factors

People in physically demanding occupations may need earlier transition plans or alternative employment pathways.

Watch for Future Legislation

Congress may still enact further changes, including tax adjustments or benefit formula revisions.

What Comes Next

The new schedules for the retirement age shift will be phased in over several years, and policymakers anticipate additional debate about Social Security reform. Many analysts say a long-term solution will require a mix of measures—including revenue adjustments, targeted benefit expansions, and continued gradual age changes.

In the meantime, experts urge workers to monitor updates and plan proactively. As Alicia Munnell of Boston College noted, “Social Security will remain a foundation of retirement income, but workers should expect more responsibility for bridging the gap.”