Federal officials have confirmed that replacing the current cost-of-living adjustment (COLA) formula with a new index would likely boost annual benefit rises for millions of retirees and disabled Americans. Yet the proposed Government Confirms One COLA Change remains stalled because of fiscal, legislative and structural hurdles within the Social Security Administration (SSA) system.

Government Confirms One COLA Change

| Key Fact | Detail |

|---|---|

| Alternative index under review | The Consumer Price Index for the Elderly (CPI-E) would replace the current CPI-W. |

| Historical impact | CPI-E-based COLAs would have averaged ~0.3 percentage points higher per year between 1984-2006. |

| Why not implemented | Cost to trust fund, requirement for Congressional legislation, methodological concerns. |

Understanding the Current Formula and the Proposed Change

How the Current Formula Works

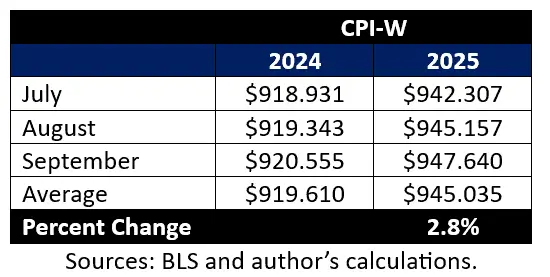

The SSA currently uses the Consumer Price Index for Urban Wage Earners and Clerical Workers (CPI-W) as the basis for its annual COLA, designed to preserve purchasing power of beneficent checks year-to-year.

What the Proposed “KW4” Formula Encompasses

The alternative index — the CPI-E (Consumer Price Index for the Elderly) — measures inflation experienced by households where at least one member is aged 62 or older. It gives greater weighting to categories such as healthcare and housing, which older Americans spend a larger portion of their budget on compared to working-age households.

In short: the CPI-E tends to rise slightly more in most years than the CPI-W. CRS research found that between 1984 and 2006 a hypothetical CPI-E-based COLA would have been on average 0.33 percentage points higher per year than the CPI-W-based COLA.

Demographic Impact: Who Stands to Gain — And How Much

Illustrative Example

Consider a retired household receiving $2,000 per month today. Under the current CPI-W formula, if the annual COLA is, say, 2.5%, their benefit rises to $2,050. With a CPI-E variant adding an extra ~0.3 percentage points, the benefit might instead rise to $2,056. That equates to roughly $72 additional in the first year and more in subsequent years via compound growth.

Who Gains the Most

- Recipients in early retirement or long retirement horizons: Extra growth accumulates over time.

- Low-income retirees who rely heavily on fixed benefit income: A small percentage difference translates to meaningful dollars.

- People with above-average healthcare/housing cost burdens: Because CPI-E weights those categories more heavily.

Who Gains Less or Faces Uncertainty

- Newly eligible beneficiaries or younger workers: The effect is modest in a single year and less visible without long-term horizon.

- Those in regions with slower cost growth in the categories weighted heavily by CPI-E: Regional variations reduce the relative benefit.

Long-Term Cost and Solvency Projections

Switching to CPI-E would increase benefit growth modestly each year, but cumulative effects over decades are significant. Congressional researchers estimate that for a 20-year retiree, the difference could amount to thousands of additional dollars in lifetime benefits.

However, the same estimates warn that the extra cost would accelerate the depletion of Social Security trust funds unless offset by higher revenues or slower benefit growth elsewhere. According to the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, adjusting the COLA formula upward without reform would reduce the margin for solvency by a measurable percentage.

Why the Proposal Is Not Being Enacted

Fiscal Constraints

The Social Security trust fund faces a projected shortfall in the early 2030s if no reforms are enacted. Boosting benefits with CPI-E would increase payouts at a time when policymakers say they must control costs to preserve long-term viability.

Legislative and Political Challenges

Changing the formula requires Congressional legislation. Despite repeated introduction of bills to adopt CPI-E, none has advanced to final passage. Advocacy groups note that “bill after bill gets stalled” because benefit increases “cost money and raise expectations.”

Methodological and Administrative Concerns

The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) characterises CPI-E as an “experimental” index with limitations: smaller sample size, use of urban data not fully tailored to older households, potential discount-pricing discrepancies.

Moreover, some experts argue that inflation measurement may overstate costs due to substitution bias—meaning consumers shift purchases when prices rise—thus undermining the case for higher COLAs.

Competing Priorities

Policymakers face many reform options: raising payroll tax caps, adjusting retirement age, means-testing benefits. Many in Congress argue that until those larger structural reforms are settled, incremental changes like switching to CPI-E should wait.

Global Benchmarking: How Other Nations Index Benefits

In several developed countries, retirement benefits are tied to inflation measures more closely tailored to older adults. For example:

- The United Kingdom uses the “Triple Lock” (highest of CPI inflation, wage growth or 2.5%) for its state pension.

- Canada’s Old Age Security is indexed to CPI-U but provinces may adjust for cost differences among seniors.

While not identical to CPI-E, these models show that indexing benefits to older-adult cost patterns is a viable international practice—but they also reflect that trade-offs (cost, longevity, demographics) exist everywhere.

Implementation Mechanics: What Would Be Required

- Drafting legislation: A bill must specify adoption of CPI-E, its weightings, transition rules (grandfathering vs new beneficiaries).

- Committee review: In both Senate Finance Committee and House Ways & Means Committee, hearings likely.

- Scoring by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO): Must estimate cost over 10-, 20-, 75-year horizons.

- Offset plan: Typically, legislation needs revenue offsets or benefit adjustments to pass.

- Implementation phase-in: The BLS and SSA would need rule-making, data system changes, and public-education campaigns.

- Monitoring and evaluation: Regular review of how the new index tracks older-adult inflation.

Given these steps, even if passed in 2026, the first COLA under CPI-E might not appear until 2028 or later.

Stakeholder Perspectives

Advocacy Groups

The non-profit Senior Citizens League estimates that a retiree who claimed benefits in 1999 has lost nearly $5,000 in cumulative benefits because CPI-W underestimates inflation compared with CPI-E. They argue that switching formula is overdue.

Policy Researchers

Dr. Jane Thompson, senior fellow at the Center for Retirement Research (CRR) at Boston College, says:

“Switching to CPI-E would improve fairness for older-adult spending patterns—but unless matched by revenue reforms it risks accelerating trust‐fund depletion.”

Government Officials

A spokesperson for the SSA says: “We continue to monitor inflation measurement and index alternatives. Any change must consider long-term solvency and legislative direction.”

Fiscal Conservatives

Some lawmakers argue that benefit growth should be moderated until the program’s financing is secured. One staffer with the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget commented:

“Indexing to CPI-E without offsets would reduce capacity for reform and may shift burden to younger workers.”

Risks, Trade-Offs and Unintended Consequences

- Increased taxes or premium hikes: To pay for higher benefits, payroll taxes could rise or Medicare premiums could climb.

- Inflation-spiral fears: Some argue indexing to a higher inflation measure could contribute indirectly to upward wage/price feedback loops.

- Regional variation mismatch: CPI-E uses national weights; local cost pressures may still differ heavily.

- Preferential treatment perception: Some groups may argue retirees would receive higher raises than working-age households, raising fairness questions.

- Transition complexity: If change only applies to new beneficiaries, existing ones may feel disadvantaged; if applied universally, cost is greater.

Related Links

New York Residents May Receive $400 Payments — Full Eligibility Details Inside

Deadline Today — Octapharma Data Breach Claims Worth Up to $5,000 Close Shortly

What Beneficiaries Should Watch

- October SSA announcement: The annual COLA is typically announced each October. Any mention of indexing change should appear then.

- Legislative tracking: Bills titled like “Fair COLAs for Seniors Act” or similar may indicate slow progress toward CPI-E adoption.

- Trust fund reports: Annual trustees’ reports often provide solvency forecasts and note cost implications of indexing changes.

- Future inflation reports: If healthcare and housing inflation accelerate, pressure for index reform may increase.

- Budget offsets: Watch for proposals to raise taxes or limit benefits elsewhere—those may accompany indexing reform.

While the COLA change to CPI-E offers a path to more accurately reflect the inflation experienced by older Americans, lawmakers must weigh benefit adequacy against long-term sustainability and fiscal constraints. With trust-fund pressures mounting and multiple reform proposals underway, the fate of index reform remains uncertain—but the debate is likely to sharpen in the years ahead.

FAQ About Government Confirms One COLA Change

Q: Would switching to CPI-E immediately raise my benefit next January?

A: No. Unless Congress passes legislation, the current CPI-W-based formula remains in place for the next COLA.

Q: Would the change apply to new beneficiaries only or everyone?

A: Legislation could decide—some proposals suggest only future beneficiaries, others include all. No decision yet.

Q: Does this affect Medicare premiums or other programs?

A: Not directly. But if benefit costs rise via CPI-E, policymakers might adjust premiums or taxes elsewhere to offset costs.

Q: Why can’t the SSA just adopt CPI-E on its own?

A: Because the COLA formula is set in law. Only Congress can change from CPI-W to CPI-E.

Q: Is CPI-E guaranteed to always be higher than CPI-W?

A: No. While CPI-E has averaged higher historically, there are years when CPI-W rose more.