The Social Security Age Change, which raises the Full Retirement Aage (FRA) to 67 for anyone born in 1960 or later, becomes fully effective in 2026. This final step in a decades-long reform reshapes when Americans can claim full retirement benefits and will influence financial planning for generations.

Experts say the shift reflects broader demographic pressures and will significantly affect how future retirees approach savings, work, and long-term security.

Social Security Age Change Finalized

| Key Fact | Detail |

|---|---|

| New Full Retirement Age (FRA) | 67 for everyone born in 1960+ |

| Earliest Claiming Age | 62 (still unchanged) |

| Maximum Delayed Benefits Age | 70, with delayed-retirement credits |

| Who Is Affected | Younger Boomers, Generation X, Millennials, Gen Z |

| Purpose | Strengthen trust-fund solvency amid aging population |

Understanding the Finalized Social Security Age Change

The United States has officially completed its long-planned rise of the Full Retirement Age to 67, marking a significant shift in federal retirement policy. The Social Security Age Change affects millions of workers who had expected to retire under earlier rules and now must adapt to a later benchmark for full benefits.

According to the Social Security Administration (SSA), the move is meant to reflect longer life expectancy and slow the financial strain on the Social Security trust funds as the population ages. For workers planning retirement over the next two decades, this change adds new complexity to decisions around saving, investing, and working longer.

Why the Retirement Age Is Increasing

A Reform Rooted in the 1980s (KW2)

The FRA increase originates from the bipartisan 1983 Social Security Amendments, enacted during a period of financial crisis for the system. Lawmakers approved a gradual shift to safeguard solvency while avoiding sudden disruptions. FRA climbed slowly—from 65 to 66, then to 67—over more than four decades.

As Dr. Laura Jameson, a Social Policy Professor at the University of Michigan, recently explained in an interview, “The 1983 law designed this change to unfold over generations. The intent was to stabilize Social Security with minimal political and personal shock.”

Increased Life Expectancy — but Not for Everyone

While average U.S. life expectancy increased significantly between the 1940s and early 2000s, recent research shows major disparities. Studies from Harvard University and the Brookings Institution indicate that higher-income Americans live far longer than lower-income workers, meaning the FRA shift affects groups unevenly.

One Brookings researcher noted: “A higher retirement age disproportionately cuts lifetime benefits for lower-income workers, who tend to have shorter lifespans and fewer savings options.”

How the Change Alters Retirement Planning for Millions

Claiming at 62 Still Possible—But More Costly

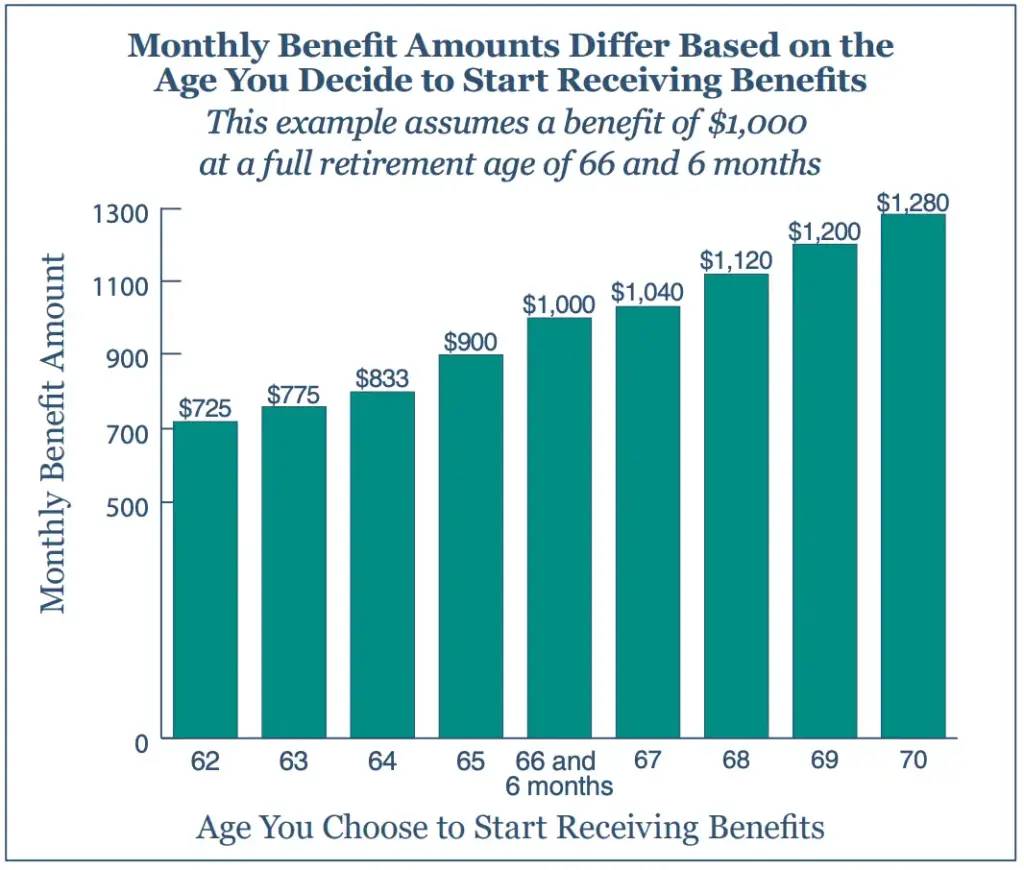

Workers can still claim Social Security at age 62, but the new FRA means doing so results in a larger permanent reduction—about 30 percent—compared with claiming at 67. Early claim reductions are permanent, meaning workers cannot “catch up” later.

FRA 67 Is Now the Central Benchmark

At 67, workers will receive their full calculated benefit. The change means workers must delay retirement or accept reduced income. SSA officials have emphasized that “FRA remains the point at which workers face neither a penalty nor a bonus.”

Delaying to 70 Offers Significant Gains (KW4)

Delaying retirement beyond FRA produces an additional annual credit—about 8 percent per year—until age 70. For many healthy workers with long life expectancy, delaying can significantly increase lifetime income.

Who Is Most Affected by the New Rules

Younger Baby Boomers

Americans born between 1960 and 1964 are the first fully impacted by the FRA 67 rule. Many are already approaching retirement and must adjust timelines or financial expectations.

Generation X (KW3)

Gen X is widely considered the most vulnerable generation financially. Research from the Pew Research Center indicates that Gen X households have lower median retirement savings than Boomers did at the same age. FRA 67 increases pressure on this group to save more aggressively or work longer.

Millennials and Gen Z

For younger generations, FRA 67 is the norm. However, they face additional uncertainties: potential further age increases, rising living costs, student loan burdens, and volatile housing markets.

Economic and Workforce Implications of a Higher Retirement Age

Labor Market Consequences

Economists caution that raising the FRA may keep older workers in the labor force longer. This could intensify competition for jobs in some sectors while worsening shortages in others, such as healthcare, education, and skilled trades.

Impact on Physically Demanding Jobs

Workers in physically strenuous occupations—construction, manufacturing, agriculture, and caregiving—tend to retire earlier due to health concerns. For them, delayed FRA effectively forces reduced benefits.

As one labor advocate stated: “Policy increases life expectancy on paper, but real workers in demanding jobs don’t always live longer—or work longer—than past generations.”

Disability Claims May Rise

Research from the National Bureau of Economic Research indicates that when retirement ages increase, disability applications tend to rise. Workers unable to continue working but too young for FRA often turn to disability benefits as a last resort.

Trust-Fund Solvency and the Policy Debate Ahead

The Solvency Challenge

The Social Security Trustees Report projects that the Old-Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) trust fund may face depletion within the next decade without legislative action. FRA 67 slows, but does not eliminate, the funding gap.

Ideas on the Table

Lawmakers are divided on next steps. Policy ideas include:

- Lifting or removing the payroll tax cap

- Introducing a “minimum benefit” for low earners

- Adopting CPI-E, an inflation measure designed for seniors

- Raising the FRA further to 68 or 69

- Means-testing benefits for high-income retirees

Analysts warn that future reforms will likely affect younger generations more dramatically.

What Financial Experts Recommend for Future Retirees

Begin Planning Earlier

With FRA later, workers need more time to build savings. Advisors recommend revisiting retirement plans every few years and adjusting contributions, especially during peak earnings years.

Run Scenarios Based on Health and Longevity

Workers should consider both their personal health and family history. For those with longer expected lifespans, delaying benefits can pay off significantly.

Maintain a Mixed Income Strategy

Experts emphasize diversifying beyond Social Security. Combining retirement accounts, savings, partial work, and investments helps reduce reliance on government benefits.

International Comparisons Add Important Context

Other developed nations, including the United Kingdom, Germany, Japan, and Australia, have recently raised—or plan to raise—their retirement ages in response to aging populations. Some countries tie retirement age automatically to life expectancy.

The U.S. has not taken that step, but some lawmakers argue it could offer a more predictable long-term approach.

Related Links

New FRA Rule Takes Effect — Why Claiming Social Security at 62 Can Reduce Lifetime Benefits

SNAP November Payments — Will Benefits Arrive on Time? Here’s What We Know So Far

With the Social Security Age Change now finalized, the landscape of retirement planning in the United States enters a new era. The rise to FRA 67 reflects demographic shifts and financial pressures that will continue shaping policy debates. While the change provides modest stability for Social Security, many future retirees must adapt by planning earlier and preparing for longer working lives.

FAQ

1. Does the new FRA reduce my total benefits?

Claiming earlier reduces lifetime benefits, and later claiming increases them. FRA 67 itself does not reduce your base calculation.

2. Will the earliest claiming age of 62 change?

No current legislation changes age 62, though some proposals have suggested adjustments.

3. Could the FRA increase again?

Yes. Some policymakers have proposed raising it to 68 or 69, but no such law has passed.